1/1

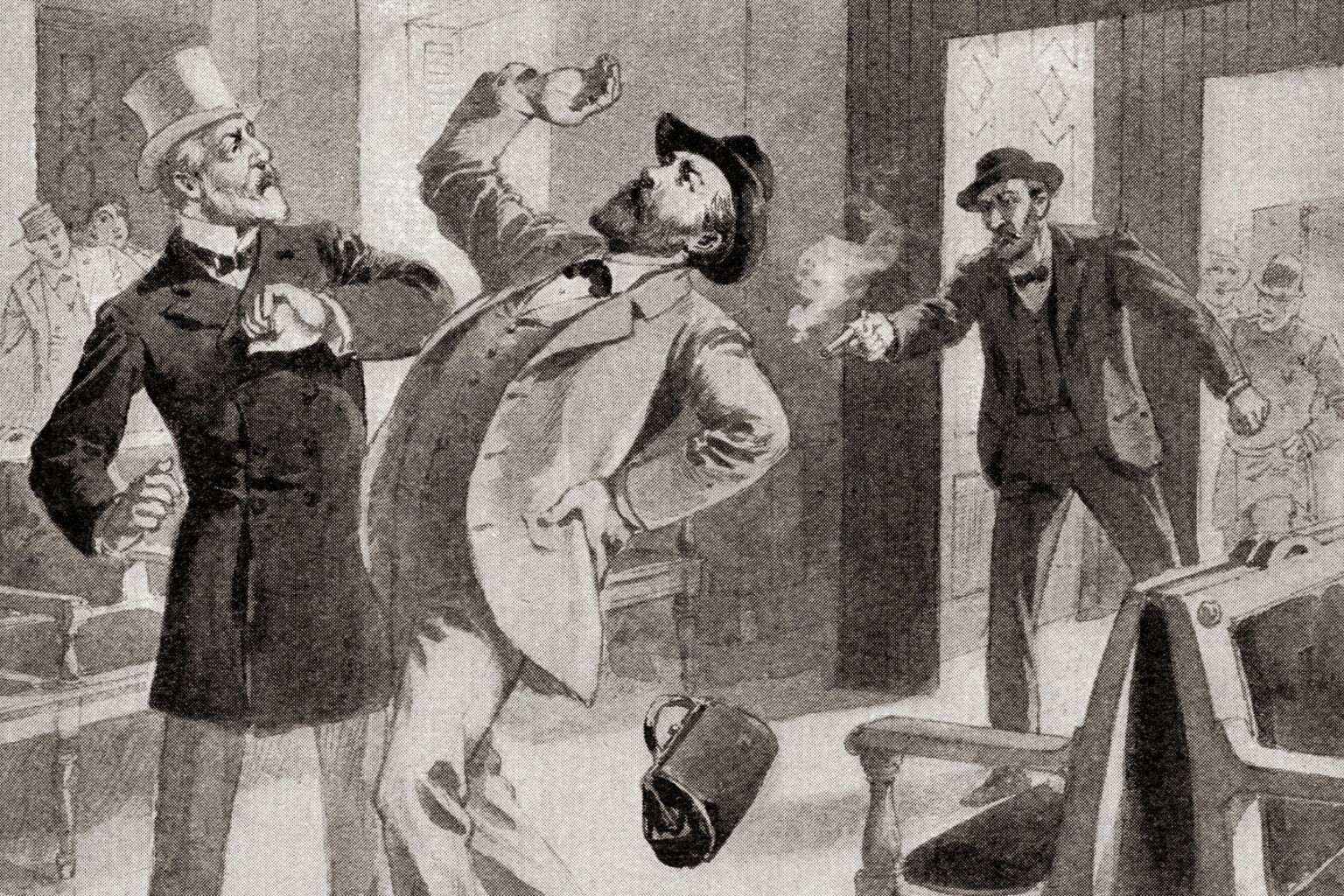

Chaos and Infection: The Assassination of President Garfield On July 2, 1881, shortly after 9:30 a.m., President James Garfield, the 20th president of the United States, was shot at Washington’s Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station by Charles Julius Guiteau, a mentally unstable lawyer seeking political reward. Garfield, traveling with Secretary of State James Blaine, had no Secret Service protection. Like Lincoln in 1865, Garfield was vulnerable. Guiteau, who studied the station for days, carried a .442 caliber British Bulldog revolver and fired twice. The first bullet shattered Garfield’s right humerus. The second lodged in his back near the pancreas and kidneys, passing within millimeters of the aorta. Chaos erupted as travelers screamed, trunks toppled, and dozens froze. Blaine knelt beside Garfield. Guiteau shouted, “I did it! I just shot the president. I had to save the Republican Party!” Doctors led by D. Willard Bliss repeatedly probed Garfield’s wounds with unsterilized fingers and instruments during the first weeks. Bliss said, “I can find it with my finger if it is anywhere to be found,” spreading infection that caused abscesses and sepsis. Alexander Graham Bell tried to locate the bullet with a metal detector, but bed springs distorted results. Garfield endured 80 days of fever, abscesses, and severe weight loss, reportedly saying, “I never expected to live to see the end of this.” Newspapers reported daily, and tens of thousands followed updates nationwide. Garfield died September 19, 1881, 79 days after being shot. Vice President Chester Arthur assumed office. Guiteau was tried, convicted, and hanged June 30, 1882. The assassination exposed presidential security weaknesses and prompted the Pendleton Act of 1883, establishing merit-based federal employment. Repeated probing of Garfield’s wounds caused infection, contributing to the 30–40% mortality for major bullet injuries, turning a survivable wound fatal. #History #USHistory #America #USA

Washington, District Of Columbia • 24 days ago

Barry

Those dastardly Republicans..haven't changed an iota..

23d

Corcoran, CA

Reply

3

Torby 4096

As a child, we lived in Freeport IL for a couple years. The large back yard joined with the rest of the neighborhood to make a huge play area for the children. Two little girls lived in the big house over there that was said to be haunted because the man who killed Lincoln once lived there. We had the right house, but the wrong president. I was never in the house, but I was on the front porch. If you Google, you can see the house with the big front porch where sometimes we played. My sisters knew the girls better than I did.

23d

Bartlesville, OK

Reply

1

Dianne Rosa

I met a decendant of President Garfield. When he walked into the room it felt like a living history was in front of me. He was the spitting image of his grandfather, big, burly with a huge personality. I'll never forget it.

22d

Dover, DE

Reply(1)

christoh

..

23d

Reply

More comments ...

write a comment...