1/6

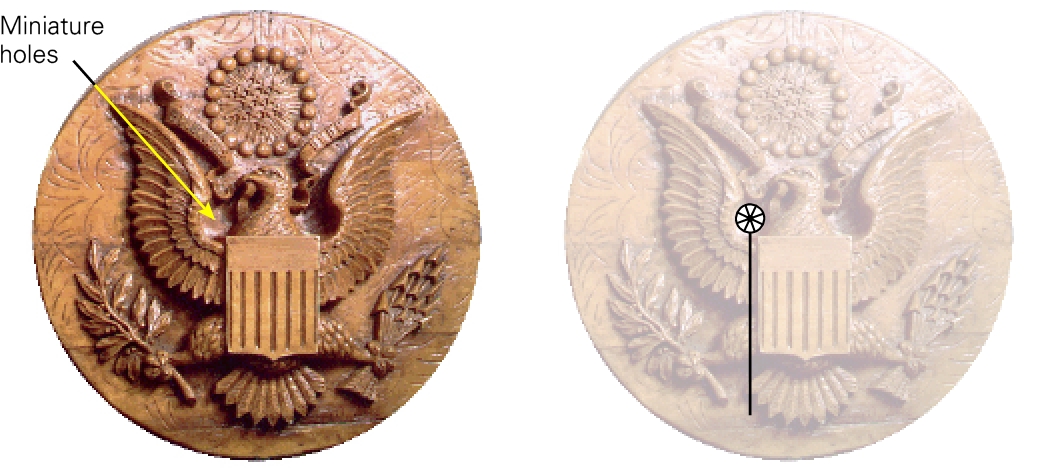

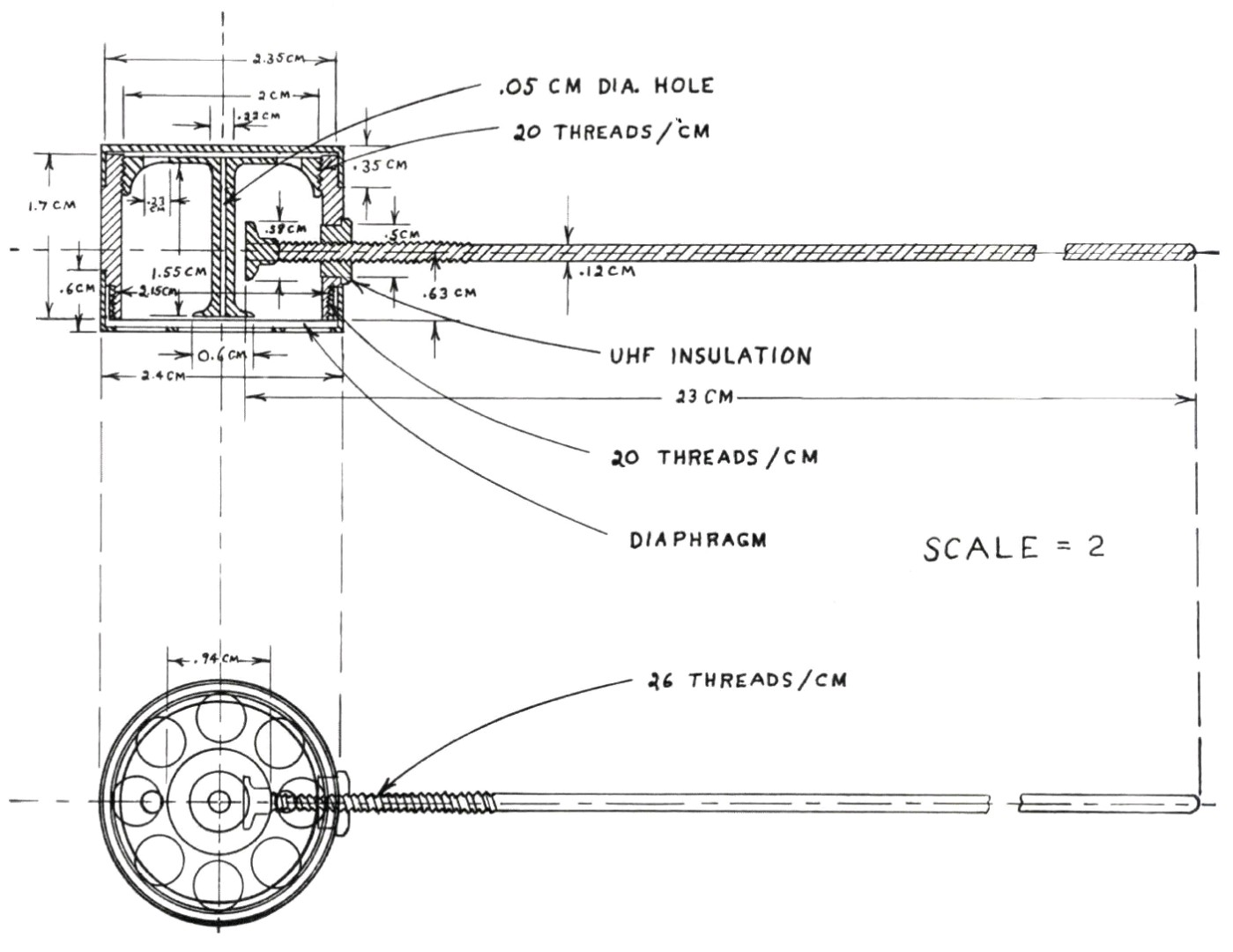

The Thing: The Soviet Spy Bug That Shook U.S. Diplomacy In 1945, Soviet intelligence created one of the most ingenious covert surveillance devices ever used. Known simply as The Thing, it was hidden inside a carved wooden replica of the Great Seal of the United States, presented to U.S. Ambassador W. Averell Harriman in Moscow as a gesture of goodwill. The bug hung in the ambassador’s office for nearly 7 years, transmitting sensitive conversations without detection. Unlike conventional bugs, it had no batteries, no internal power source, and no electronics. It was a passive resonator. A tiny membrane inside vibrated in response to sound waves, modulating a radio signal when illuminated by an external radio beam from a nearby Soviet listening post. U.S. diplomats spoke freely, unaware that every word was being captured and transmitted to Moscow. Its design made it extremely difficult to detect. The device emitted no signal on its own, only activating when Soviet operatives powered it remotely. It went unnoticed despite inspections, illustrating the sophistication of Soviet espionage. Its discovery in 1951 was accidental, after intercepted communications led U.S. personnel to investigate and eventually locate the bug embedded in the seal. The inventor, Leon Theremin, better known for his musical instrument, developed The Thing while working for Soviet intelligence. Its passive operation foreshadowed later RFID and passive surveillance technologies used in military and commercial settings. Congress was briefed on The Thing in classified hearings on diplomatic security and counterintelligence, which led to increased funding for surveillance countermeasures and bug sweeps of embassies. The device was publicly revealed in 1960 by U.S. Ambassador Henry Lodge Jr. at the U.N., demonstrating Soviet espionage capabilities. Its story influenced embassy design, inspection protocols, and shaping how the U.S. protects sensitive information to this day. #History #USHistory

19 days ago

chris johnson

USA

19d

Columbus, MS

Reply(1)

More comments ...

write a comment...