1/1

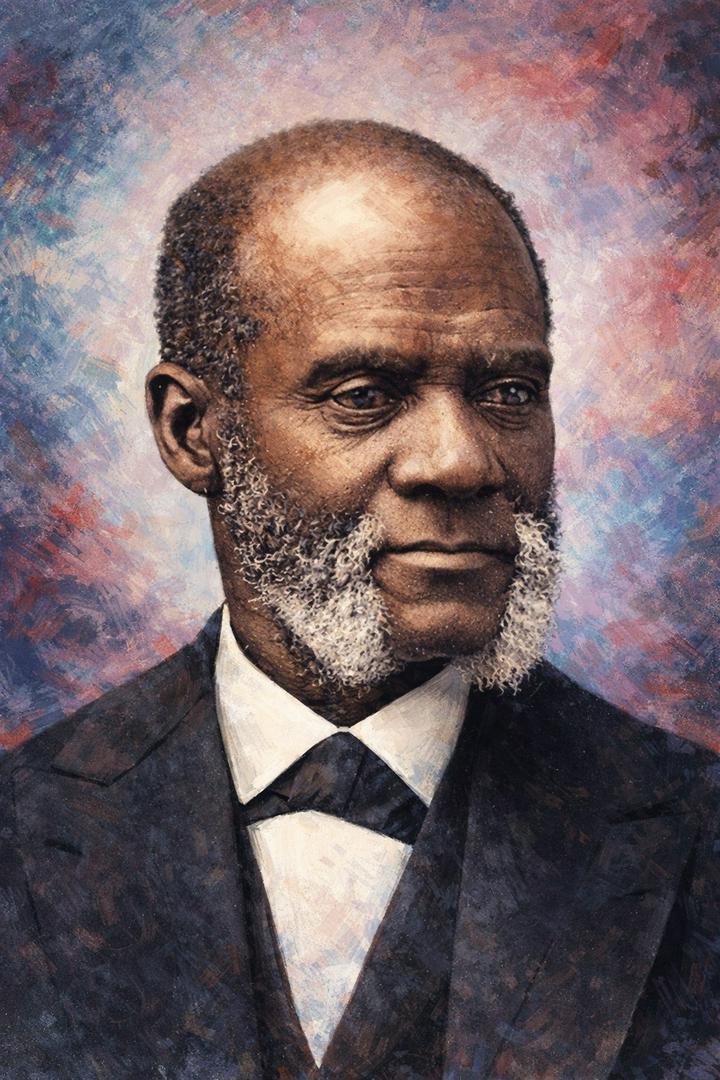

Henry Highland Garnet died in 1882, but the ideas he left behind never softened with time. Born into slavery in Maryland, Garnet escaped with his family as a child and grew into one of the most uncompromising voices of the abolitionist movement. Unlike many reformers who relied primarily on moral persuasion, Henry Highland Garnet spoke directly to those still enslaved and urged resistance to bondage, including the possibility of physical resistance when submission meant permanent captivity. His most famous address, delivered in 1843 and titled An Address to the Slaves of the United States of America, openly called on enslaved people to reject submission and reclaim their freedom themselves. At the time, this message was considered dangerous even among abolitionists. Many feared it would provoke violence or undermine gradual reform efforts, while others believed it crossed a line they were unwilling to approach. The speech was controversial enough that it was rejected by the National Negro Convention when first presented. Garnet’s position placed him at odds with more widely accepted figures of the era, yet it reflected a reality many were reluctant to confront. Enslavement was enforced through violence, and appeals to conscience alone had failed to dismantle it. Garnet did not glorify suffering or chaos. He questioned whether a system built on force could be undone without confrontation. After emancipation, Garnet continued in public service and, in 1881, was appointed United States Minister Resident and Consul General to Haiti, becoming one of the earliest African American diplomats to serve abroad. His life traced a full arc from enslavement to international representation, but it is his refusal to temper his words for comfort that keeps his legacy uneasy. Garnet forces an enduring question. When injustice is absolute, what forms of resistance are considered acceptable, and who gets to decide where that line is drawn. #HenryHighlandGarnet #AbolitionHistory

Maryland • 22 days ago

Delona Sundermann

I wish people will read history but not want payment from people that had nothing to do with generations ago. People stop themselves from becoming what God gave them. People fail themselves and are accountable for themselves

21d

Mesquite, NV

Reply(2)

2

More comments ...

write a comment...